A while ago, I was inspired to look at my family’s mortality (as you do). I began by looking at my female ancestors, and though it’s taken a while I have now repeated the exercise for the men in my tree — to my 3x great grandfathers. Beyond them I have only scant and less reliable information.

On my father’s side

My paternal grandfather

My paternal grandfather David Leslie (1899-1964) died when I was very young, but he lived with my family for a time before his final illness so I have very strong memories of being the focus of his attention, and feeling much- loved and very special. He died of lung cancer, complicated by bronchitis, on Boxing Day 1964.

Great grandfathers

My dad’s paternal grandfather, David Leslie (1877-1940), died aged 73 of arteriosclerosis and cerebral thrombosis. He had spent his working life as a kilnsman in the potteries of Kirkcaldy, Fife.

Dad’s maternal grandfather Thomas Elder (1874-1929), died aged 54, of colon cancer which had metastasised to his liver. He had been an ironmonger most of his working life, and there is a family rumour – which I haven’t been able to verify – that he suffered gas poisoning in World War I.

2x great grandfathers

George Leslie (1822-1902), is one of the mysteries in my family tree; a man whose early life (probably spent in the counties of Banff and Morayshire) is largely un-documented. With the introduction of statutory records to Scotland in 1855, I am able to trace his later life with more certainty. He died at his home in Kirkcaldy, with 79 given as his age on the death certificate. Cause of death was recorded as senile decay and acute bronchitis. He had worked as a carter and labourer.

Rankine Gourlay (1845- 1903) lived a relatively short but interesting (for a family historian) life. He joined the Merchant Navy as a fourteen year old, and I know from maritime records that he sailed on several occasions to Sydney, Australia, and Valparaiso in Chile. He contracted syphilis during this time and was admitted to the Fife and Kinross Lunatic Asylum in July 1889, after threatening behaviour towards his wife and one of his daughters. He was discharged to the Kirkcaldy Combination Poorhouse in October 1891, where he remained until his death, aged 57, in July 1903. Cause of death was recorded as general paralysis and syphilis.

William Elder (1844 – 1933) was born Dysart, Fife. In the 1861 census, his occupation was listed as pottery labourer. Three years later when he married Elizabeth Penman in Dunfermline, Fife, he was listed as a colliery engine driver. This is the occupation he seems to have maintained until the 1891 census, when he was listed as Colporteur – or a travelling salesman of books, particularly bibles and religious tracts. He seems to have maintained this line of work for the rest of his life, being described as a travelling salesman on his wife’s death record in 1920 and a commission agent on his own death certificate in 1933. He was 89, and his cause of death was given as bronchitis, fracture of femur and cardiac failure.

Andrew Nicholson (1838-1894) also lived most of his life in Dysart, except for a period during the early 1860s when he and his wife Susan Forbes moved to Glasgow. Andrew’s occupation on the 1861 census was given as Engine Smith. After the family returned to Fife (prior to the 1871 census) he seems to have begun working in his wife’s father’s grocery business. His death certificate records him as a “retired grocer and engineer” and shows cardiac disease as the cause of death. He was 56.

3x great grandfathers

John Leslie (dates unknown). The only records I have that mention John Leslie relate to his son George.

George was baptised twice; the first time on 3 August 1822 in Portsoy, Banff and the second time in New Spynie, Moray on 31 August 1822. The first baptism was in an Episcopalian church; the second church of Scotland. John is named as his natural father on both records. The Episcopalian baptism refers to him as a “farm servant to Captain Cameron in Banff” and this is the only clue I have to his identity.

When George Leslie married in 1857, John is named and shown as living. He doesn’t appear to have married George’s mother Elizabeth Robertson, and without more information, I haven’t been able to trace him through census, church or statutory records.

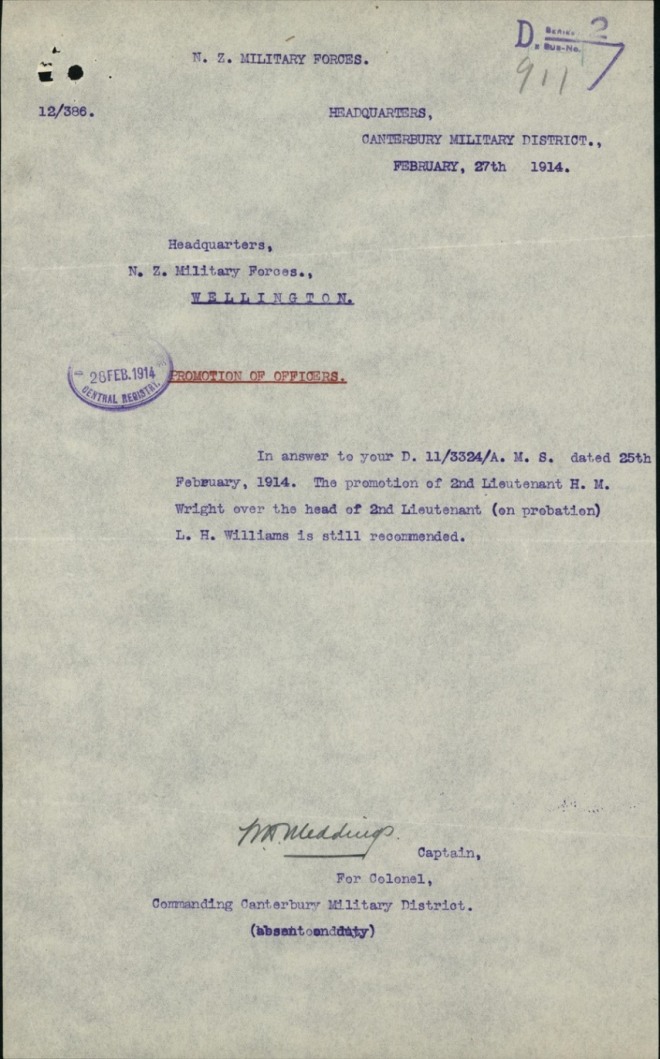

William Trail (1789-1867) was born in Perthshire but lived most of his adult life in Auchtermuchty, Fife. He worked as a handloom weaver and died a pauper aged 67. His death certificate lists cause of death as “general debility from ?? life”. I’m unclear what the missing word is, but it could be widowed?

Death certificate, William Trail. Cause of death “general debility from ….” Record accessed from Scotland’s People.

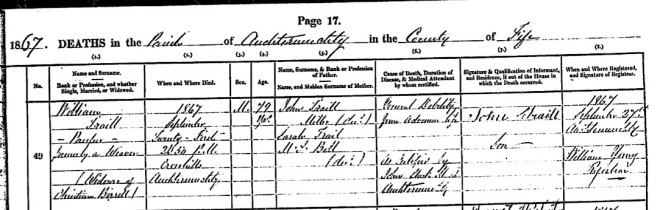

Thomas Gourlay (1809-1867) lived his entire life in Abbotshall, Fife. He was a master tailor, probably learning his trade from his father George. Thomas died aged 58; his death certificate lists cause of death as “accidental death by falling into a well.” The local newspaper report described the incident as taking place very late in the evening as Thomas was visiting a neighbour. In the dark he apparently fell into the neighbour’s well, and although rescued, died shortly afterwards.

Fifeshire Journal, 31 October 1867. Report of the death of Thomas Gourlay. Image: British Newspaper Archive

Alexander Gerrard (1803-1883) died aged 80 of bronchitis. He had worked in his early years as a handloom weaver, but by his forties had become a gardener/labourer. This was shown as his occupation on his death certificate.

Thomas Elder (1809-1894) died aged 85 of senile decay. He had lived his entire life in Fife, most of it in Dysart. He was a weaver, working first of all on a handloom – probably from home with other members of his family, then later in a linen mill. The 1871 census records him as still working – aged 71.

Robert Penman (1816-1872) died of smallpox, aged 56. He was born in Dalgety, Fife and died in nearby Dunfermline. The occupation – from census records and his death certificate was coal miner.

Alexander Nicholson (-1848) Alexander achieved a considerable rise in wealth and status in what seems to have been a relatively short life. When he married Mary Tod in 1827 his occupation was shown as weaver. By 1835 he appears on the Register of Voters as a Land Surveyor and land owner. At the time of his death – of typhus — he had accumulated a considerable portfolio of real estate and held the positions of Inspector of the Poor and Baron Baillie in the parish of Dysart. I am not certain of his birth year, but the 1841 census gives his age as 35 (which means between 35 and 40) and his obituary suggests that he was a relatively young man.

David Forbes (1807-1861). Like his daughter’s father in law (and apparently his friend) Alexander Nicholson, David Forbes also died relatively young (age 54). His cause of death was liver disease, which may have been related to his occupation as a publican and spirit merchant.

My mother’s male ancestors

My maternal grandfather

Mum’s dad, David Skinner Ramsay (1901-1973), was a diabetic, who lost both lower legs to gangrene. My strongest memory of him is of vying with my cousins to sit in his lap while he propelled his wheelchair around. I don’t have a death certificate for him, but I believe that his death was related to his diabetes.

Great grandfathers

David Skinner Ramsay (1877-1948), was a coal miner who died aged 71 of a spinal tumour. I know very little about him, but in the photographs I have he was always smiling.

David Skinner Ramsay and Mary Fisher; their fiftieth wedding anniversary. Image: Ramsay-Leslie family archive

Alexander Cruden (1890-1970). Because he died in 1970, I haven’t yet been able to access my great grandfather’s death certificate. I know that as a very young man he worked as a coal miner, and that he was seriously wounded in WWI. He had one leg amputated above the knee and spent many years as an occasional in-patient at the Edenhall Hospital for Limbless Soldiers and Sailors. During the 1930s and 1940s he ran the Fife Arms pub in Milton of Balgonie.

2x great grandfathers

Stewart Cameron Cruden (1863-1934) Stewart worked as a factory hand and labourer, moving his family from Dundee, through various addresses in Fife until they settled for a time in Dysart where he became a coal miner. Sometime in the 1920s Stewart, his wife Isabella Wallace and their youngest son (also Stewart), emigrated to the United States, where they lived in Bayonne, New Jersey. The family had returned to Scotland by 1934 when Stewart died of a cerebral haemorrhage and cardiac failure, aged 70.

Alexander Black (1856-1926) died at the age of 69 in Dysart, Fife. He was born in nearby Kinglassie and had spent most of his working life as a coal miner. He was a widowed at the age of 43 and did not remarry. He died of chronic hepatitis.

John Ramsay (1854-1905) died aged 51 in the Fife & Kinross Asylum, Cupar. His cause of death is recorded as general paralysis and acute congestion of brain. Both incarceration in the asylum and the cause of death are reminiscent of Rankine Gourlay (above), who was hospitalised in the same asylum with a diagnosis of syphilis. It seems possible that John Ramsay was similarly infected.

George Fisher (1858-1934) died aged 76, suffering from colon cancer. He had been widowed twice, and had spent his working life employed in the linen factories of Kirkcaldy, where he lived his entire life.

3x great fathers

David Skinner Ramsay (1817-1871) died aged 54, of typhoid fever. Compared to many of my ancestors, his life was more varied – both geographically and in terms of his work. He seems to have progressed from agricultural labourer as a young man, to a Master Miller with his own mill by his mid-thirties. This career was short-lived and he was bankrupt by the age of forty. He subsequently worked as a grain agent, but by the time of his early death, he was a Carter

The father of 2x great grandmother, Isabella Westwater is unknown.

John Fisher ( – 1888). John’s birth and early life are a bit of a mystery. The first record I have of him is the OPR record of his marriage in 1848 to Margaret Lindsay. From that, I know he was a flax-dresser, of Dysart parish. His death certificate shows his age as 62, and cause of death as bronchitis. His occupation was still flaxdresser.

Peter Westwood (1824-1893) was born in Glasgow, but seems to have settled in Fife by his mid-twenties. He remained there until his death aged 70. Cause of death is recorded as liver disease. He had worked as a shoemaker.

Alexander Cruden (1839-1896) was baptised in Moneydie, Perthshire and seems to have lived most of his life between Perthshire and Dundee. Census records show he progressed from working as a weaver, to a lathe operator, eventually becoming a cabinet maker. He was married three times and died aged 56, of heart disease.

Donald Wallace (1830-1872) was a farm labourer, born in Kirkmichael Perthshire. He died of pneumonia aged only 41, leaving behind a wife and five small children. The youngest was born only weeks before his death.

James Black (1820-1897) worked as an agricultural labourer around the rural area of Kinglassie, Fife. He died aged 77 of chronic bronchitis, his death certificate shows that he was still working.

Thomas Boswell Bisset (1831-1902) about whom I’ve written a great deal, died aged 70 of catarrh and pneumonia. He worked as a carter.

Some reflections and conclusions

Doing this exercise made me incredibly grateful for excellent Scottish record-keeping – in particular statutory records, which began in 1856.

When I looked at the age-at-death data for my female ancestors, I was struck by how many lived very long lives. Two made it into their 90s while five of the 27 I have information about lived into their 80s.

Perhaps more surprisingly, four of those five were born in the first half of the 19th century (1812, 1824, 1832 and 1839), a period during which average life expectancy for Scottish women was less than 50 years.

For my male ancestors, such longevity was a little less frequent. None made it into their nineties, although (appropriately) two of my Elder ancestors came close. Thomas Elder (3x great grandfather) made it to 89, while his son William Elder died aged 85. Sadly, their descendants — my great grandfather Thomas Elder and his daughter, my grandmother Susan Elder – both died relatively young; at 54 and 50 respectively.

The average age at death across the four generations of men I looked at was 66 years (72.5 for the women), and the median age 69.5 (73 for the women).

Causes of death ranged from accidents to “old age”, with bronchial conditions proving to be the most frequent cause, closely followed by cancers, heart and liver disease and strokes/cerebral hemorrhage.

With few exceptions, these men were born into poor, working class, landless families. Most were engaged in manual labour of some kind, though a few were skilled craftsmen and several ran businesses. Only four were listed on their death certificates as retired.

Of the twenty five I have birth data for, all were born in Scotland and 18 were born in Fife. Of the remaining seven, five were born in the neighbouring counties of Angus or Perthshire. Only Peter Westwood and George Leslie seem to have arrived in Fife from further afield; Lanarkshire, and Banff in the northeast of Scotland respectively.

I have place of death data for twenty eight out of thirty. Of these, twenty six died in Fife – twenty one in and around the town of Kirkcaldy. Only two died out of the county; one each in Angus and Perthshire.

Almost without exception, these men lived their entire lives within about a 40km radius of Kirkcaldy. As far as I know, only five ever left Scotland for any time, and for three them, it was to fight in World War I.

In many ways, there is nothing extraordinary about my assorted grandfathers. They lived fairly typical lives for their time, leaving only faint traces of themselves in written records. But however ordinary, they deserve to be acknowledged and remembered. This post is a very small contribution towards that end.