Enlistment portrait: Eric Andrew Gray (20 October 1895 – 27 March 1918), with sisters Doris and Ethel Gray c. 1916. Image: Gray family archive (courtesy of Peter Duncan).

Today is ANZAC day; the day that New Zealanders and Australians commemorate our countrymen and women who have died in wars, and honour our returned servicemen and women.

What is ANZAC Day?

The date marks the first landing of Australian and New Zealand troops (ANZACs) on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey; 25 April 1915. The ANZACs were part of a larger Allied force comprising also British, French and other Commonwealth troops which aimed to capture the Dardanelles (strategically, the gateway to the Bosphorus and the Black Sea) from its Turkish defenders.

The campaign lasted eight months; cost over 130,000 lives (Turkish and Allied) and ended with the exhausted and depleted Allied armies withdrawing from the peninsula in December 1915, having totally failed to achieve their objective.

Around 8700 Australians and 2779 New Zealanders died at Gallipoli. Although this pales in comparison with losses in other WWI battles (842 NZ soldiers died on one day alone at Passchendaele), Gallipoli has come to symbolise the beginnings of a national identity in both countries. (Sources: The Gallipoli Campaign, and 1917: Arras, Messines and Passchendaele: New Zealand History)

Our boys

When I began researching my son’s paternal (New Zealand) ancestry, I knew from my father in law that two members of his family had served in WWI: his father Wallace Oliver Gray (1892-1981), and Eric Andrew Gray (1895-1918), Wallace’s younger brother. (see note below on posts about the brothers)

Enlistment portrait; Wallace Oliver Gray. c. 1917. Image: Gray family archive (courtesy of Peter Duncan).

I’ve since discovered that Wallace’s wife, Merle Wright, had two brothers who served also; Henry Marshall Wright (1891-1915) and Fred Nathaniel Wright (1894-1972).

Henry (Harry) Wright’s military service is particularly poignant here, as he died in the Gallipoli campaign — on 7th August 1915, at Chunuk Bair.

Chunuk Bair: “the high point of the New Zealand effort at Gallipoli”

Most New Zealanders will be familiar with the name Chunuk Bair. Geographically, it is a hill on the Sari Bair ridge, Gallipoli.

Map showing Sari Bair offensive, Gallipoli 1915. Source: “Sari Bair offensive, August 1915 map”, New Zealand History.

Militarily, it was a strategic objective. Troops from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and Maori Contingent were ordered to take and hold the hill against the Turks.

Militarily, it was a five day battle that ultimately failed; costing (officially) 849 New Zealanders’ lives, with a further 2500 men wounded (Counting the cost of Chunik Bair, Stuff, August 8 2015). Overall, there were an estimated 30,000 casualties, Turkish and Allied.

Historically, it was another example of the poor military planning and leadership that characterised the entire Gallipoli campaign. (Counting the cost of Chunik Bair, Stuff, August 8 2015). The objective was unrealistic, promised support did not materialise, the men weren’t adequately supplied with essentials — like water — and poor communication meant that many casualties were the result of “friendly fire.”

Valley leading out of Chunuk Bair; rocky, exposed, barren and hot. Image Source: Australian War Records Section, Australian Memorial.

Culturally, Chunuk Bair has become synonymous with Kiwi fighting spirit, bravery, and endurance against the odds. It was the only piece of the peninsula the Allies managed to capture beyond what they occupied in the April landings. The Kiwis held Chunuk Bair for two days before being ordered to withdraw.

Harry Marshall Wright

Born in Ohoka, Canterbury, on 19 August 1891, Harry Wright was the eldest of eight children born to Sidney Robert Wright and Jessie Susan Harris (about whom I’ve written a little here). His younger sister, Merle Matilda Wright would become my son’s great grandmother (marrying Wallace Gray in 1926).

When he left for Gallipoli, on 17th April 1915, Harry was a 1st Lieutenant in the Canterbury Infantry Regiment. He had enlisted in the regular army on 24th November 1914, aged 23, having already been a member of the Territorial Cadets since his school days at Christchurch Boys High School.

Portrait of Harry Wright from the Auckland Weekly News, 1915. Source: Online Cenotaph record.

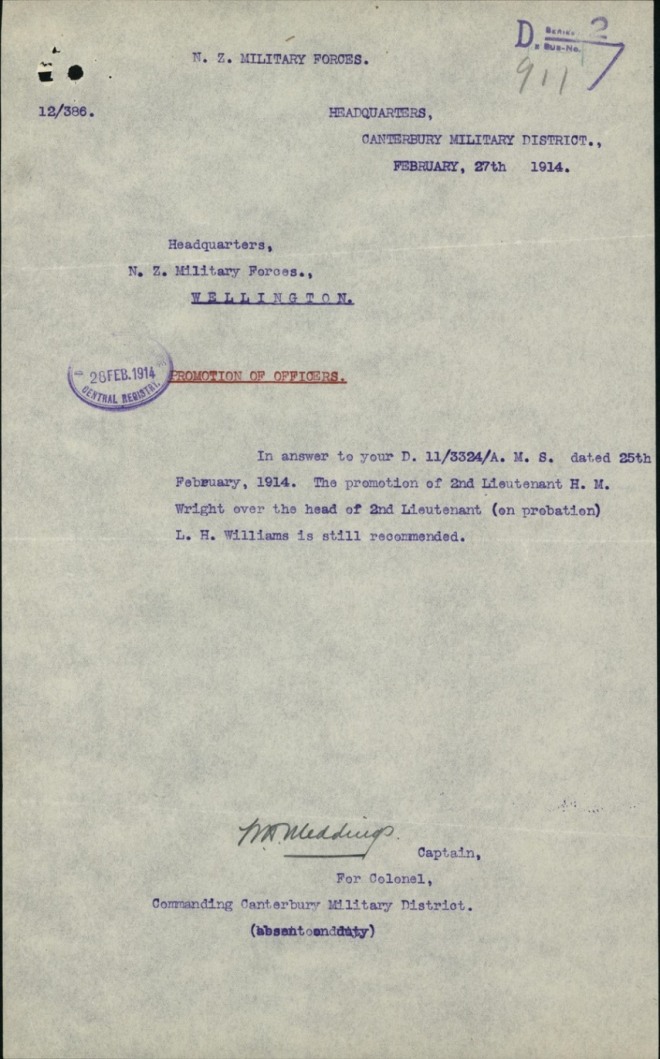

He had been commissioned as a second-lieutenant in the coast defense detachment of the Canterbury Regiment in 1912 and in 1914, was promoted to 1st Lieutenant — apparently in preference to another officer who “should” have received the promotion.

Letter confirming the promotion of Harry Wright, 1914. From Military Service Record, held at Archives New Zealand.

According to his military records, at the time of his enlistment, Harry Wright worked as a treasury clerk for the Christchurch City Council. He was unmarried, five foot nine and a quarter inches tall, weighed 154 pounds, had a dark complexion, brown eyes and hair, and had a scar on his chin.

An account of the offensive from the Canterbury’s Official History

I’ve read several accounts of the Chunuk Bair offensive, including that from the official history of the Canterbury Regiment, published in 1921. At the risk of taking information out of context, I think it is worth quoting from this document which shows the whole assault to be confused and problematic.

The task of the Canterbury Battalion was to … attack the Turkish trenches on Rhododendron Spur from the west … After these trenches were captured, and the two columns of the brigade were in touch, the Canterbury and Wellington Battalions were to attack the summit of the Sari Bair Ridge … with the peak of Chunuk Bair inclusive to Wellington and on the latter’s extreme right.

The time necessary for the Mounted Rifle Brigade to clear the entrances to the ravines having been under-estimated, there was considerable congestion and confusion… so that it was 1 a.m. (on August 7th) before the Canterbury Battalion was (in position) … whereas according to the time-table for the attack … the battalion should have reached the Dere before 11 p.m (August 6th).

There had been no opportunity for reconnoitring the ground over which the advance was to be made … on the afternoon of the 6th. Consequently the advance … was difficult, and the difficulty was increased by the darkness of the night. The battalion lost its way completely in a branch of the main ravine, and had to retrace its steps.

On the battalion turning about, the 12th and 13th Companies, at the rear of the column, received a garbled version of the Commanding Officer’s orders to return to the main ravine, and thinking they had been ordered to go right back to Happy Valley, did so. The remainder of the battalion picked up its bearings again and moved up … to Rhododendron Spur. A great deal of time had been lost, and it was now beginning to get light. Pushing on up Rhododendron Spur, the battalion about 5.45 a.m. came in touch with the Otago Battalion, which, in spite of the fact that it had already been heavily engaged at Table Top and Bauchop’s Hill, had taken three lightly held Turkish trenches on the Spur.

The 12th and 13th Companies left Happy Valley at dawn … and had little difficulty in re joining the battalion on Rhododendron Spur. By 8 a.m. the New Zealand Infantry Brigade had reached positions which were practically on the site of the front line of the trench system held by us on the Spur till the evacuation of the Peninsula—Wellington on the north, Otago at the eastern point, and Canterbury on the south. Here the brigade dug in, under very heavy rifle and machine-gun fire, especially from Battleship Hill, and from a trench on a spur north-east of Chunuk Bair.

At about 9.30 a.m. the brigade was ordered to assault Chunuk Bair, and as neither the Auckland Battalion nor the 10th Gurkhas had been heavily engaged up till now, these battalions were selected for the attack. On their advancing at 11 a.m., they immediately came under heavy fire; and though the Auckland Battalion reached a Turkish trench about a hundred and fifty yards east of our most advanced positions, its casualties were so heavy that it could get no further.

At 12.30 p.m. the Canterbury Battalion received orders to hold its trenches with half the battalion, and with the remaining half to support Auckland in a new attack. The 1st Company was left to garrison the trenches … and the remainder of the battalion moved forward and lay down in the open. It at once came under heavy shrapnel fire from the left flank and suffered severe casualties, losing one officer killed and six badly wounded, in addition to three officers previously wounded.

The battalion’s casualties during the four days’ fighting had been very heavy, as the list below shows:—

| Officers. | Other Ranks. | |

|---|---|---|

| Killed | 4* | 65 |

| Wounded | 8 | 258 |

| Missing | — | 11 |

| 12 | 334 |

Like many who died at Gallipoli, Harry Wright has no marked grave.

He is remembered on the Chunuk Bair (New Zealand) Memorial within the Chunuk Bair Cemetery at Gallipoli — a young man with a bright future; a second-generation Cantabrian who volunteered to travel across the world to fight for an empire his working-class grandparents had emigrated from in search of a better life.

A young man who never had the chance to grow old.

The title of this post is a line from the Laurence Binyon poem For the Fallen, (1914) from which one stanza has come to be known as the Ode of Remembrance; recited at memorial services such as ANZAC Day and Remembrance Day.

The full stanza reads:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

__________

(1) I have written about the Wallace and Eric Gray in previous posts:

Anzac Day Remembrance: Gray brothers, Hororata

Death of a Soldier: 27 March 1918

Eric Andrew Gray: following the trail of a young soldier

Six Word Saturday: “… just like a broken brick heap”

“A small shell burst in a trench near me”

“We got dug in about five feet deep by dinner time and then Fritz started to shell”,

Reblogged this on Zimmerbitch and commented:

For ANZAC Day, one of our family’s WWI stories.

I know how strongly you feel about ANZAC Day by my own feelings on our Memorial Day. This is a magnificent post to honor those men!

Thanks GP. It took a while to write this; mostly trying to understand Chunuk Bair from accounts of what happened. I don’t think I’ll ever be much of a military historian 🙂 but even I could see that an out-of-touch leadership, combined with a lot of small errors and bad decisions resulted in catastrophe.

Sadly, I agree.

Extremely interesting read, Su! And to think that it is your boy’s family you’re researching here, makes it become so much more real.

Thank so much Sarah. I keep looking at the photos of those young men and seeing T and the boy in their faces. And I can’t but admire the women — mothers, wives and sisters. T’s grandmother lost a brother and brother in law, and both her husband and another brother had been to war (plus friends and cousins probably). Those who came home carried terrible scars that sometimes blighted their whole lives, and surely the lives of the women around them.

I often think that these women of former generations had so much more strength and determination than us, and I wonder why that might be. Probably because they simply had to… It´s not as if our lives are less impressive or anything but we lack a certain bravado or something like that, in my mind.

Scars of war always affect the whole family, don´t they? Not only the visible ones or loss of limbs, but the invisible ones as well. So many families carry the wounds and the wounded long after a war has ended, and that´s what makes all the terrible destruction even worse, I think…

I think you are right. In so many ways, everyday life was harder for earlier generations. Women had fewer rights, less freedom, lower expectations of education, more kids, fewer gadgets to help them do housework. People generally had to survive without benefits and formal assistance. Not to diminish our generation’s experiences, but I think many of us are quite sheltered from some of the harsher life experiences of our ancestors — including war (thankfully). Though, as you say who knows what will happen next! xxxxx

Maybe it would be good for us, if we all had to spend a couple of weeks up to 3 months in similar conditions. Like an experimental workshop for body and soul. It wouldn’t be exactly the same of course, since we would knew that there is a foreseeable end to it but maybe it would make us change our lifestyles and attitudes etc. I probably would like to participate in something like this 🙂

There are actually quite a lot of documentaries (German) that illustrate these kind of things, like how was it to live around 1900 or in the Bronze Age. They took on “normal” people who tried reliving these times and filmed them at it. They are quite fun to watch – especially when your sitting on a couch and eat something they didn’t have at that time 😉

xxxxxxx

I rather like your idea. I know the documentaries you mean — I have seen English-language versions, but always about living a long time in the past. I think it would be really good for kids my son’s generation to live like their grandparents. My parents didn’t have a telephone or a car until they were in their early 30s and had been married for over 10 years. During their childhoods, they had to share a bedroom with siblings, walk or bicycle to get around and wouldn’t ever have expected to get multiple gifts for birthdays or Christmas. My dad went to work when he was 14; my mother 15. It’s not that long ago, but a completely different world. It would be so interesting to see m son go without his phone even for a day! xxxx 🙂

I know! So much has changed in a mere generation or two! My mum always tells me how they had to use a communal toilet, or go out on the street to a telephone box if she wanted o apply for a job. And gifts! They would have been lucky to get one at all! Mostly it was just hand-me-downs. So short after WWII her family struggled very much.

Maybe we should all try to go a day without our phones. Or make that a week 😉 I think many people would go berserk! 😀 There´s actually a hotel in Spain, Barcelona I think, where guests give up their phones, iPads, notebooks etc at the reception where it is safely locked in, to guarantee a stress free holiday. Of course, if they don´t manage at all, they can have their things back, but most people try this “cold turkey”. The first days are supposed to be awful but after that it gets better. It would be easier for those of us who remember a time without all these gadgets I think though… 😉 xxxxxxxx

Telephone boxes!!! I remember the first flat T and I had in England had no telephone, and we had to use the phone box outside. It was close enough to the house that I think we could give people the number, and answer it if it rang. I remember organising job interviews while standing in the box, juggling pen and paper against the glass walls. We lived in a very small village, and it was the only phone box there. It’s lucky most of the other residents had their own phones.

I love the idea of the hotel where you check in your electronic devices — and even more so because it’s in Barcelona.

🙂 xxxxx Hope you have a great week.

Sounds exactly what my mum did 😉 And look where we are now – carrying around our phones as if it were the most normal thing in the world, and even making pictures with them 😉

Hope you have a wonderful week too! 🙂 xxxxxxxx

Thanks. The sun is shining and I feel like I need to spend as much time in the fresh air as I can before winter really arrives.

I´m glad that I haven´t had yet to live in times of war, and I dread the day that it might be a possibility with all the dickheads running their states around the world…

Thank you for writing this—another chapter of history about which I was shamefully ignorant. Am I right that there was a movie called Gallipoli? Was it about this battle? And here’s a probably stupid question—what does ANZAC stand for? I assume one of the As and the NZ are for Australia and New Zealand, respectively–is the AC Army Corps? Or something like that?

War truly is hell, and yet it still goes on, and young people die as older people sit back and send them into battle.

Thanks Amy. There’s really no reason you should know about Gallipoli; even British people tend not to know about it, and British troops were there (and in command … much grinding of teeth). It was such a disaster the British War Office tried to suppress information about the campaign. Interestingly, Rupert Murdoch’s father was instrumental in making the UK government aware of how badly it was going, and having the general in charge replaced.

There is an Australian movie called Gallipoli (with a young Mel Gibson), and yes, it does focus on the Australian’s part in the same offensive as Chunuk Bair. The Australians fared worse than the NZers — gaining no ground and suffering very heavy casualties.

ANZAC stands for Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, and although we still use the term, I don’t think there is any formal connection between our defense forces any more.

The more I read about past wars, the more futile it all seems.

Thanks for all the explanations. Sometimes there are reasons to use force—to stop genocide, for exampe—but often even that just leads to more killing.

Agreed. It’s so difficult to envisage the downstream consequences of any action, no matter how just it seems.

Ah dear Su. What to do? Thanks for the post though. ANZAC day itself is now conflicted.

Isn’t it! I can’t see the tensions disappearing anytime soon, sadly.

Fascinating post. Like Amy, I didn’t know much about ANZAC until two years ago. I happened to be in Istanbul when the 100 anniversary ceremony was being held at Gallipoli. I met a number of people who came from Australia and New Zealand to take part in the dawn ceremony.

Thank you. There was a national ballot for places at the 100th anniversary at Gallipoli, so the people you met were very lucky to have been able to attend.

Lovely post. That photo of your father-in-law reminds me so much of your son and your husband. Such a nice photo of him. The quality is really fabulous, it’s been well preserved. I recently learned that one of my Scottish cousins perished in 1918 in action in Flanders. He is the first family member I have come across that died during war. When I read his probate file I felt as if someone had punched me in the gut. I was so saddened to read his will and then learn of his death as such a young man. I’m also surprised that I haven’t come across this before in my tree. I have plenty who fought, but so far only the one who died. My reaction to reading about him gave me a new level of empathy for the families of those whose lives were lost. This cousin was so far back, I didn’t really feel much of a connection and still I was quite upset to read of his death. I don’t even have a picture of him. Your post is a lovely way to honor your family members who fought and survived or perished.

Thank you so much. I was given these photos quite recently by a distant cousin, and they are such a treasure.

On my side of the family (the Scottish side) we were also spared many casualties. My great grandfather was wounded in France in WWI (I don’t know the details), and had both legs amputated. His younger brother died in WWII in the Arctic Convoys, but it seems our other servicemen survived with lesser injuries. I understand what you mean about feeling upset. I don’t think we have to have a close connection to empathise with those who lose loved ones — and those who live with the scars they bring home.

This is a great post, full of information and history. Well done and I love the photos of that time, so different to now.

Thanks Debbie. It took ages to write (or at least edit) because I kept getting side-tracked wanting to tell other, related stories. I read quite a lot about the Australians involvement in the Sari Bar offensive. Aaaagh!! You probably know so much more about this than me … but seven Victoria Crosses awarded to Aussie troops during those four days; and horrendous casualties.