I hadn’t thought about it too much until recently, but I am definitely a family historian rather than a genealogist. While I’m interested in tracing and recording my lineage, I’m much more interested in understanding the lives my ancestors led and the societies that shaped them.

This realisation has come about in part because of a conversation I had with my dad a couple of days ago. It’s a major source of disappointment to him that, to date, none of his grandchildren have his surname. Although I’m not married – so still use the “family” name – my partner and I chose to give our son his surname rather than mine.

A rare Leslie family photo. My dad is on the left holding my brother. I’m seated on Uncle Tom’s knee. My favourite uncle ever, Tom Leslie was my grandfather David Leslie’s younger brother.

I also have two brothers. One of them changed his middle and surnames years ago so his three children don’t meet with Dad’s approval either. My other brother has recently adopted a child and my father was jubilant because he finally has a grandchild with the “right” name.

My relationship with my dad is prickly at the best of times, and I have to admit to feeling quite pissed off with him. He probably didn’t mean it, but it really sounded like his biological grandkids were somehow second-best because they won’t carry on “the name.” Our conversation reminded me that when I first talked to him after my son’s birth, he was decidedly sulky over the naming of my baby.

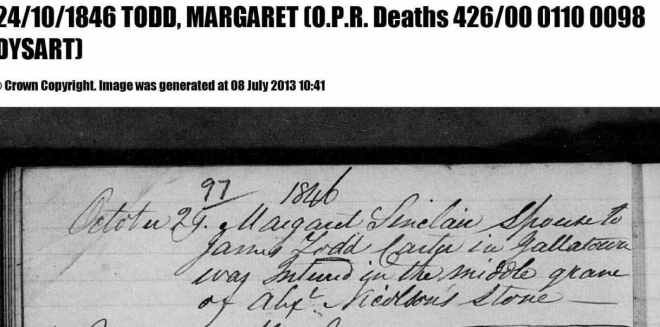

I was wondering if that’s maybe why I haven’t made much of an effort to trace the Leslie branch of my family, so I went back to my family tree and noticed that it is 146 years today since the birth of my great grandfather David Leslie.

David Leslie was born on July 23td 1867 in Auchtermuchty, Fife, to George Leslie and Janet Trail (who sometimes appears in the records as Jessie, and with her surname sometimes shown as Traill or Jrail).

Birth extract: David Leslie (my great grandfather), 23 July 1867)

David appears to have been the fifth of seven children born to George and Jessie, although it seems that Jessie also bore a daughter, Christina Trail, the year before her marriage to George.

The 1871 census shows the family living in Auchtermuchty, with Jessie as the head of the household.

I found this record a while ago, and had assumed that George must have died. Since then however, I’ve found his death certificate – dated 1902. George also appears alongside Jessie in all the subsequent census records up until his death.

A search on Scotland’s People shows sixteen people called George Leslie in the 1871 census, and given what I know about George, six of these are possible matches. At the moment, I’m not keen to use up credits trying to find him, so until I can get to the library and use Ancestry, his whereabouts on census night will have to remain a mystery.

By the 1881 census, the family had moved to Kirkcaldy. The family consisted of George and Jessie, plus Jessie’s daughter Christina, George jr. William, Elizabeth, Isabella, David, John and Jessie jr. The three younger children were all at school, though it’s likely that my great grandfather would have left at fourteen to go to work. George seems to have spent his working life as a labourer.

By the 1891 census, David was working in one of Kirkcaldy’s potteries as a kilnsman. This is the occupation also shown on the extract of his marriage certificate in 1892, when he married Isabella Gourlay. David’s mother Jessie was one of the witnesses to the marriage, along with Isabella’s brother Thomas Gourlay. I know that Isabella’s father Rankine Gourlay would not have been at the wedding, as he was a patient at the Fife and Kinross Lunatic Asylum at the time.

David and Isabella had six children; my grandfather David being the fourth.

David Leslie sr. died in 1940 when my father was eight years old. My great grandmother Isabella died in February 1961, just months before I was born.

As always, the more information I have about ancestors, the more I want to know. But I can’t say that I am any more interested in the Leslie family than any other branch of my tree. I do want to know why George wasn’t at home on census night 1871, and I’d like to know when he made the move from Elgin to Dundee. I’m curious about whether he had siblings and who his parents were, but I’m not driven by any need to prove some sort of lineage. My research will, I think, always be guided by how interesting I think characters are and how much I can learn about their stories.

I can’t help thinking my dad would probably disapprove of this too.