Enlistment portrait: Eric Andrew Gray (20 October 1895 – 27 March 1918), with sisters Doris and Ethel Gray c. 1916. Image: Gray family archive (courtesy of Peter Duncan).

Today is ANZAC day; the day that New Zealanders and Australians commemorate our countrymen and women who have died in wars, and honour our returned servicemen and women.

What is ANZAC Day?

The date marks the first landing of Australian and New Zealand troops (ANZACs) on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey; 25 April 1915. The ANZACs were part of a larger Allied force comprising also British, French and other Commonwealth troops which aimed to capture the Dardanelles (strategically, the gateway to the Bosphorus and the Black Sea) from its Turkish defenders.

The campaign lasted eight months; cost over 130,000 lives (Turkish and Allied) and ended with the exhausted and depleted Allied armies withdrawing from the peninsula in December 1915, having totally failed to achieve their objective.

Around 8700 Australians and 2779 New Zealanders died at Gallipoli. Although this pales in comparison with losses in other WWI battles (842 NZ soldiers died on one day alone at Passchendaele), Gallipoli has come to symbolise the beginnings of a national identity in both countries. (Sources: The Gallipoli Campaign, and 1917: Arras, Messines and Passchendaele: New Zealand History)

Our boys

When I began researching my son’s paternal (New Zealand) ancestry, I knew from my father in law that two members of his family had served in WWI: his father Wallace Oliver Gray (1892-1981), and Eric Andrew Gray (1895-1918), Wallace’s younger brother. (see note below on posts about the brothers)

Enlistment portrait; Wallace Oliver Gray. c. 1917. Image: Gray family archive (courtesy of Peter Duncan).

I’ve since discovered that Wallace’s wife, Merle Wright, had two brothers who served also; Henry Marshall Wright (1891-1915) and Fred Nathaniel Wright (1894-1972).

Henry (Harry) Wright’s military service is particularly poignant here, as he died in the Gallipoli campaign — on 7th August 1915, at Chunuk Bair.

Chunuk Bair: “the high point of the New Zealand effort at Gallipoli”

Most New Zealanders will be familiar with the name Chunuk Bair. Geographically, it is a hill on the Sari Bair ridge, Gallipoli.

Map showing Sari Bair offensive, Gallipoli 1915. Source: “Sari Bair offensive, August 1915 map”, New Zealand History.

Militarily, it was a strategic objective. Troops from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and Maori Contingent were ordered to take and hold the hill against the Turks.

Militarily, it was a five day battle that ultimately failed; costing (officially) 849 New Zealanders’ lives, with a further 2500 men wounded (Counting the cost of Chunik Bair, Stuff, August 8 2015). Overall, there were an estimated 30,000 casualties, Turkish and Allied.

Historically, it was another example of the poor military planning and leadership that characterised the entire Gallipoli campaign. (Counting the cost of Chunik Bair, Stuff, August 8 2015). The objective was unrealistic, promised support did not materialise, the men weren’t adequately supplied with essentials — like water — and poor communication meant that many casualties were the result of “friendly fire.”

Valley leading out of Chunuk Bair; rocky, exposed, barren and hot. Image Source: Australian War Records Section, Australian Memorial.

Culturally, Chunuk Bair has become synonymous with Kiwi fighting spirit, bravery, and endurance against the odds. It was the only piece of the peninsula the Allies managed to capture beyond what they occupied in the April landings. The Kiwis held Chunuk Bair for two days before being ordered to withdraw.

Harry Marshall Wright

Born in Ohoka, Canterbury, on 19 August 1891, Harry Wright was the eldest of eight children born to Sidney Robert Wright and Jessie Susan Harris (about whom I’ve written a little here). His younger sister, Merle Matilda Wright would become my son’s great grandmother (marrying Wallace Gray in 1926).

When he left for Gallipoli, on 17th April 1915, Harry was a 1st Lieutenant in the Canterbury Infantry Regiment. He had enlisted in the regular army on 24th November 1914, aged 23, having already been a member of the Territorial Cadets since his school days at Christchurch Boys High School.

Portrait of Harry Wright from the Auckland Weekly News, 1915. Source: Online Cenotaph record.

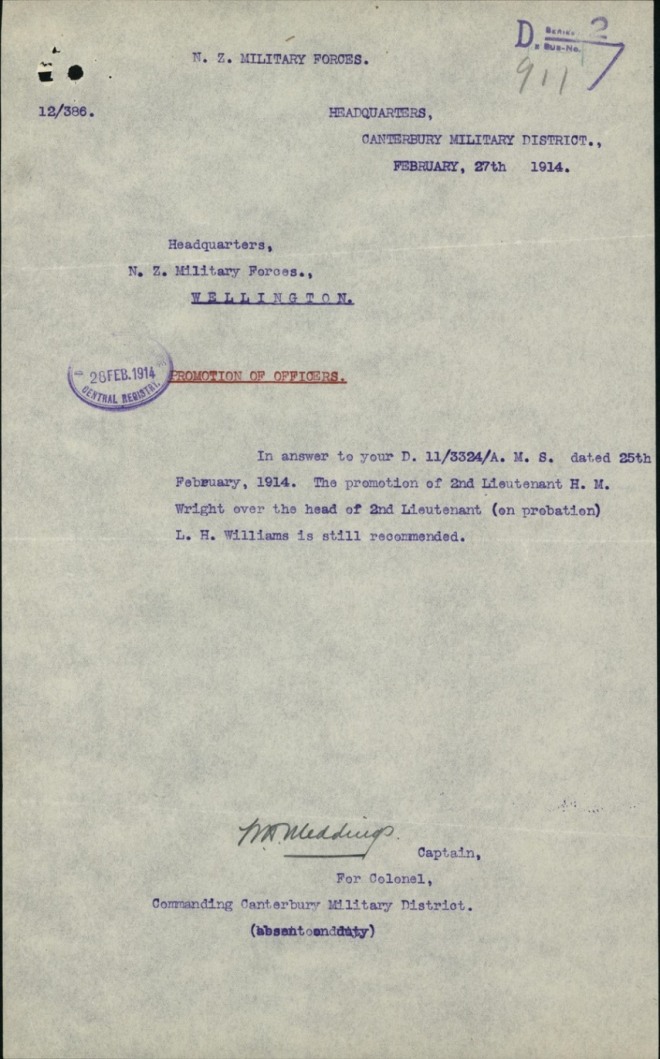

He had been commissioned as a second-lieutenant in the coast defense detachment of the Canterbury Regiment in 1912 and in 1914, was promoted to 1st Lieutenant — apparently in preference to another officer who “should” have received the promotion.

Letter confirming the promotion of Harry Wright, 1914. From Military Service Record, held at Archives New Zealand.

According to his military records, at the time of his enlistment, Harry Wright worked as a treasury clerk for the Christchurch City Council. He was unmarried, five foot nine and a quarter inches tall, weighed 154 pounds, had a dark complexion, brown eyes and hair, and had a scar on his chin.

An account of the offensive from the Canterbury’s Official History

I’ve read several accounts of the Chunuk Bair offensive, including that from the official history of the Canterbury Regiment, published in 1921. At the risk of taking information out of context, I think it is worth quoting from this document which shows the whole assault to be confused and problematic.

The task of the Canterbury Battalion was to … attack the Turkish trenches on Rhododendron Spur from the west … After these trenches were captured, and the two columns of the brigade were in touch, the Canterbury and Wellington Battalions were to attack the summit of the Sari Bair Ridge … with the peak of Chunuk Bair inclusive to Wellington and on the latter’s extreme right.

The time necessary for the Mounted Rifle Brigade to clear the entrances to the ravines having been under-estimated, there was considerable congestion and confusion… so that it was 1 a.m. (on August 7th) before the Canterbury Battalion was (in position) … whereas according to the time-table for the attack … the battalion should have reached the Dere before 11 p.m (August 6th).

There had been no opportunity for reconnoitring the ground over which the advance was to be made … on the afternoon of the 6th. Consequently the advance … was difficult, and the difficulty was increased by the darkness of the night. The battalion lost its way completely in a branch of the main ravine, and had to retrace its steps.

On the battalion turning about, the 12th and 13th Companies, at the rear of the column, received a garbled version of the Commanding Officer’s orders to return to the main ravine, and thinking they had been ordered to go right back to Happy Valley, did so. The remainder of the battalion picked up its bearings again and moved up … to Rhododendron Spur. A great deal of time had been lost, and it was now beginning to get light. Pushing on up Rhododendron Spur, the battalion about 5.45 a.m. came in touch with the Otago Battalion, which, in spite of the fact that it had already been heavily engaged at Table Top and Bauchop’s Hill, had taken three lightly held Turkish trenches on the Spur.

The 12th and 13th Companies left Happy Valley at dawn … and had little difficulty in re joining the battalion on Rhododendron Spur. By 8 a.m. the New Zealand Infantry Brigade had reached positions which were practically on the site of the front line of the trench system held by us on the Spur till the evacuation of the Peninsula—Wellington on the north, Otago at the eastern point, and Canterbury on the south. Here the brigade dug in, under very heavy rifle and machine-gun fire, especially from Battleship Hill, and from a trench on a spur north-east of Chunuk Bair.

At about 9.30 a.m. the brigade was ordered to assault Chunuk Bair, and as neither the Auckland Battalion nor the 10th Gurkhas had been heavily engaged up till now, these battalions were selected for the attack. On their advancing at 11 a.m., they immediately came under heavy fire; and though the Auckland Battalion reached a Turkish trench about a hundred and fifty yards east of our most advanced positions, its casualties were so heavy that it could get no further.

At 12.30 p.m. the Canterbury Battalion received orders to hold its trenches with half the battalion, and with the remaining half to support Auckland in a new attack. The 1st Company was left to garrison the trenches … and the remainder of the battalion moved forward and lay down in the open. It at once came under heavy shrapnel fire from the left flank and suffered severe casualties, losing one officer killed and six badly wounded, in addition to three officers previously wounded.

The battalion’s casualties during the four days’ fighting had been very heavy, as the list below shows:—

| Officers. | Other Ranks. | |

|---|---|---|

| Killed | 4* | 65 |

| Wounded | 8 | 258 |

| Missing | — | 11 |

| 12 | 334 |

Like many who died at Gallipoli, Harry Wright has no marked grave.

He is remembered on the Chunuk Bair (New Zealand) Memorial within the Chunuk Bair Cemetery at Gallipoli — a young man with a bright future; a second-generation Cantabrian who volunteered to travel across the world to fight for an empire his working-class grandparents had emigrated from in search of a better life.

A young man who never had the chance to grow old.

The title of this post is a line from the Laurence Binyon poem For the Fallen, (1914) from which one stanza has come to be known as the Ode of Remembrance; recited at memorial services such as ANZAC Day and Remembrance Day.

The full stanza reads:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

__________

(1) I have written about the Wallace and Eric Gray in previous posts:

Anzac Day Remembrance: Gray brothers, Hororata

Death of a Soldier: 27 March 1918

Eric Andrew Gray: following the trail of a young soldier

Six Word Saturday: “… just like a broken brick heap”

“A small shell burst in a trench near me”

“We got dug in about five feet deep by dinner time and then Fritz started to shell”,