The latest edition of the Fife Family History Society Journal arrived, and with it a chance to find out more about my Elder ancestors – a branch of the family I had – co-incidentally – been focusing on lately.

A snippet in the journal indicated the existence of an article from 1864 about my 4x great grandparents Thomas Elder and Agnes Thomson.

Thanks to the efficient and helpful Librarian at Kirkcaldy Galleries, I now have a copy of this article.

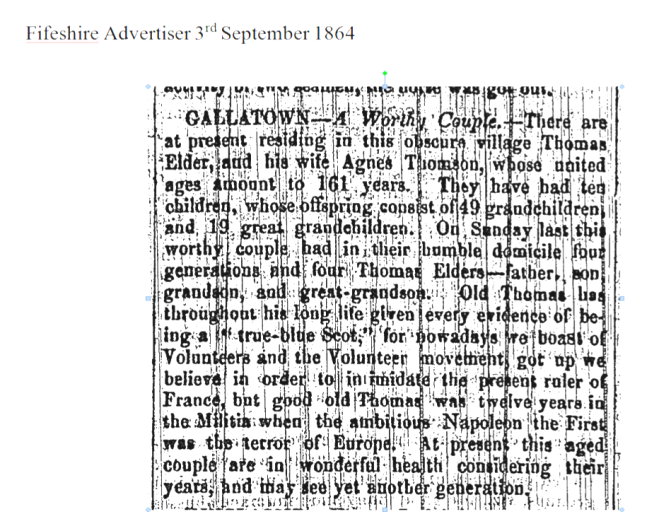

Fifeshire Advertiser, 3 September 1864. An article about my ancestors Thomas Elder and Agnes Thomson. Reproduced courtesy of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

And it’s fascinating. Apart from revealing quite a lot about 19th century journalistic style (at least in local newspapers) — “On Sunday last this worthy couple had in their humble domicile …” — it confirms a few things I already knew about these ancestors and gives me a new line of research to follow up.

The article suggests that Thomas Elder – who was born in Buckhaven, Fife on 22 November 1783 – served in the Napoleonic Wars. This is the first time I’ve had an indication of an ancestor involved in that very distant conflict, so it’s a whole new avenue of research for me.

Thomas Elder’s birth record is one of the earliest I have. It shows him to be the “lawful son” of another Thomas Elder (this story has squillions of them – elder Elders, and younger Elders and … well, you’ll see) and Isobel Dryburgh.

I know nothing about Thomas’s early life or military service, but I do know that he married Agnes Thomson, originally from Cults (also in Fife), 17 December 1805, in Buckhaven. Agnes seems have been the child of Thomas and Agnes Thomson, although I don’t have enough information yet to verify that.

I know very little about my great x 4 grandparents, except that they had at least eight children. The first record of their lives is the 1841 census. It shows them living in Gallatown, Dysart, Fife with their three youngest children; Isabella, 15, John, 14 and Orr, 12. Thomas’s occupation was given as agricultural labourer. Gallatown is about six miles from Buckhaven, and in 1841 a large proportion of the population worked as handloom weavers. Also living in Gallatown at the same time were two of Thomas and Agnes’s sons – David and James, both with wives and young children.

The 1851 census shows that Thomas’s household had shrunk to himself and his wife and his occupation had changed to carter. His older sons still lived nearby with their growing families. By the 1861 census, 78 year old Thomas was still working as a carter.

The 1864 article shown above finishes with the following lines:

At present this aged couple are in wonderful health considering their years, and may yet see another generation.

Sadly, that wasn’t to be.

Agnes Thomson died on 22 October 1870. She was 85 years old and a resident of the Markinch Poorhouse (Dysart Combination Poorhouse). The Poorhouse Governor, who was the informant of the death, described her as “wife of Thomas Elder, worker, latterly pauper.”

It is clear that after Agnes’s death, Thomas left the Poorhouse; the 1871 census shows him living with his son (also Thomas) – and his son’s family – back in Dysart.

But his respite was short-lived. Eighty eight year old Thomas Elder died on 17 February 1972, once again an inmate of the Poorhouse. Again, the informant on the death record was the Governor, who described Thomas on the register as “labourer, latterly pauper.”

I don’t yet know whether admission records for the Markinch Poorhouse have survived and whether they might tell me how this elderly couple – who seemed to have such a large family living close by – ended up dying in a Victorian institution that was designed to provide relief from destitution without ever letting those who needed it forget the prevailing ideology that it was all their own fault.

It may be that the answer was simply widespread poverty. The younger Thomas, in whose home the elder was living in 1871, was himself 61 at the time of the census. He worked as a linen weaver, while his two adult daughters who also lived there, were described as factory workers. Not an affluent family, and one that could perhaps have been tipped into destitution of its own by sickness, loss of work or some other – perhaps minor – misfortune.

So often in my search for understanding of my family I find events that make me incredibly sad. The death of small children is one such tragedy – residence in the Poorhouse is another.It seems that Thomas Elder fought for Britain over a 12 year period in his youth, raised a large family and continued to be a productve, working man until his old age. His death, and that of Agnes, makes me feel very sad.