That our names are central to our sense of identity is clear – just ask anyone whose name is regularly mis-spelt or mis-pronounced. For many of us, our names were chosen to honour ancestors or other family members, and so a link to the past and to our kin becomes a element of our selves whether we like it or not.

One of the things I’ve learned doing family history is that in Scotland, at least until the twentieth century, there existed a formalised pattern of naming children after relatives.

Judy Strachan at Judy’s Family History has explained this clearly here, but essentially it meant that first sons were named after their paternal grandfather, first daughters after their maternal grandmother, second sons – maternal grandfather, second daughters, paternal grandmother. Third children were named after their parents, and after that it seemed to be a bit more of a free for all with the other names that floated around in the family.

Children were only given middle names when the person they were named after had a different surname to theirs, in which case they usually got the person they were named after’s surname. This avoided people being given the same middle name as their surname or parents having to make something up.

Of course, not everyone followed the pattern, and high infant mortality rates meant that sometimes names one might expect to find a family are missing – or alternatively, there are two children in a family who have been given the same name after the first died.

I have “discovered” dead children by examining the birth order of great, great aunts and uncles and noticing that one was “missing” (On Chasing Ghosts). My feelings about these discoveries are always mixed; it’s difficult to enjoy the success of clever detective work when the result is a small child whose life ended only weeks or a few years after it began.

As a cultural practice, the naming pattern seems to have largely died out – although even in my generation there are vestiges of it.

And like many cultural practices, this one is both a gift and a curse for genealogists and family historians. On one hand it helps verify the likelihood that a person one is researching belongs to a particular family – on the other it can do the exact opposite as multiple cousins can often share the same name – because they share the same grandparent.

My great uncle, Stewart Cameron Cruden. Studio portrait c. 1915. Son of Alexander Cruden, grandson of Stewart Cameron Cruden, great grandson of another Alexander Cruden.

In my family, I have found some branches adhered quite rigidly to the naming pattern over many generations. My Cruden family for example, contains a veritable muddle of Stewarts and Alexanders.

Similarly, my first name – Susan – appears four times (that I’ve been able to trace so far) in alternative generations of grandmothers – back to my 4x great grandmother, Susanna Fowls who was born in 1786.

My mother, as the fourth daughter in her family was named after a great, great grandfather’s third wife, while my father – whose older brother was named after his father and paternal grandfather – seems to have had his first name chosen from outside the family (after a popular film star of the time perhaps?) He does however, have two middle names – one from each side of his family.

In my generation, I’m named for my paternal grandmother, while each of my brothers was given a first name my parents liked and a family-related middle name.

My only child was born before my obsession with family history, but even back then, I knew I wanted his name to locate him within both sides of the family. We agreed he’d have his father’s surname and that we wouldn’t lumber him with a name we didn’t like just for “family” reasons, but the boy-child has ended up with both first and middle names that have a very long pedigree in virtually every branch of my family.

My recent research into my Elder family has thrown up a very long and virtually unbroken line of Thomas Elders – stretching back to the early years of the eighteenth century (and almost certainly beyond that).

This is the farthest back I’ve traced any part of my family, and while I’ve come to a dead-end with the Elders, I have managed to trace the earliest Thomas’s wife back another generation – ironically to another Thomas.

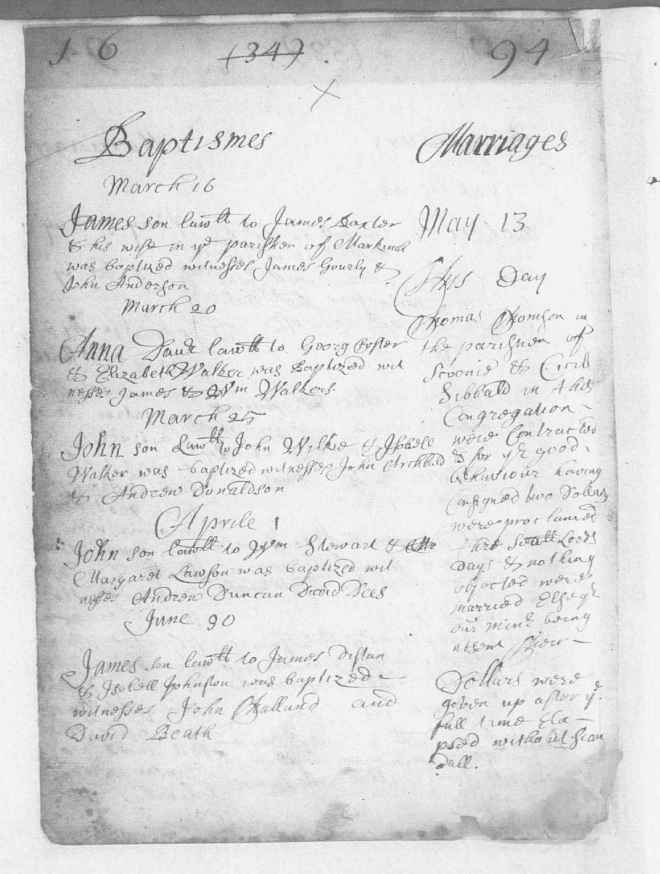

Marriage record, Thomas Thomson and Cecil Sibbald, 17 May 1694 in the parish of Kennoway, Fife. Source: Scotland’s People.

Thomas Thomson and Cecil Sibbald – my 7x great grandparents – were married on 13 May 1694, in Kennoway, Fife. To put that in perspective; in 1694 Scotland was still a sovereign nation – albeit one that shared a monarch with England. It wasn’t until 1707 that the Acts of Union were passed, combining Scotland and England (and Wales) into an entity called Great Britain. This was later changed to ‘The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’ – or the UK as we now call it.

This year of course Scotland is having a referendum on whether to leave the UK. If this is successful, my son’s Scottish cousins may be the first generation of the family to marry within an independent Scotland since their 8x great grandparents 320 years ago.

Our names are central to our identity. The Scottish practice of naming children for family members means that for many of us, part of our identity is our place in a long history of men and women who lived, worked, raised children, laughed, sang, told stories, and dreamed of a brighter future for their kids.

But it’s not just our personal names that identify us. The name of our homeland can also be an important statement about who we are. I grew up calling myself “Scottish” even though – or perhaps because – I lived half a world away. I am a New Zealand citizen these days, but I think of myself as “British” or “Scottish” – pretty much interchangeably – rather than “Kiwi.” I’m too far away from the debate to know what the feeling is amongst Scots in Scotland. Will the majority choose to re-name themselves in a political sense – or continue to call themselves “Brits.”

Come the 18th September, I guess we’ll know.

This post was written for the Daily Post Weekly Writing Challenge.

Great post and read,Su ! There is always much fuss about children’s naming and the traditions.I share your attitude and also I found Judy’s link very interesting and informative !

All the best , Doda ♥

Thank you Doda. I was very lucky to read Judy’s post quite soon after I started blogging, and it has helped me so much in my research. Cheers, Su 🙂

The information on the Thomson side is interesting as I’m tracing my husband’s family name “Thompson” it’s so elusive and winds and turns even in the US, I just can’t give up, his Mother was Norwegian and so the family declares the are fully Norwegian, I come from a family full of Scots and I’m intent on finding them is Scotland too, I just FEEL it! Sooo..plugging along and thanking you for this information as either the turn I take in that fork in the road or the one I salute as your family but still looking for mine.

Holly T.

Good luck Holly; family history is so addictive.

I’m really fortunate that ALL (yep, every single one) of my ancestors were Scots and so not only am I looking in a small geographical region, but in a country that has fabulous records which have been digitised. All the best in your searching. 🙂

Wonderful post! As you may know, I also have written about naming patterns and the Jewish traditions surrounding them. They are not quite as complex as the ones you describe—just that the child should be named for a deceased ancestor, not anyone living. I was named for my great-grandmother and have always felt a connection to this woman I never met.

Hi Amy. Yes, I read your post and thought it interesting how different cultures take different paths to achieve the same thread of connectedness. the Jewish tradition has a major advantage in allowing lots more variety in names and avoiding the situation where lots of people within a generation or two all share the same name; that is so confusing. Even by my generation I had three Uncle Daves, three Uncle Stewarts, two cousins called Elaine, two called Robert … It was so much worse for my mother and grandmother.

Yikes! And I thought I had problems with numerous Abrahams, Josephs, Rebeccas, Sarahs, etc!

I’ve just made a word cloud of the first names in my family; and that’s before I’ve started filling out the non-direct branches. I got a headache at six (or was it seven) people called Thomas Elder that I’m descended from. 🙂

Great post Su!

Scottish naming is always very interesting, I have also noticed a trend for middle names where a child is given the middle name which was the surname of a man who had married an older sister – often with families having children over the space of 20 or more years it isn’t uncommon to have an eldest daughter getting married when her mother is still having children and I have come across it a fair few times where her husband’s surname is adapted into her younger siblings name. It is quite nice really.

Hi Alex, wow, that’s a new one for me. I know what you mean about child-bearing across a long time span though; my grandmother and great grandmother had sons within months of each other. It is a lovely way to show that a son-in-law has become part of the family.

I had no idea of the Scottish naming tradition but find it so interesting. I love the idea of names trickling down the family tree over generations although I can look at the names on my own and see that that didn’t happen in my own. . My grandmother was one of eleven sisters all having names you don’t hear much any longer: Blanche, Doris, Ethel, Shirley and the like. Funny how you can pinpoint the decade almost by one’s name, at least here in the US.

Thanks. It’s true that you can date people by their name quite well. Susan was such a common name for women my generation; I went through school being one of four Susan’s, I’ve always worked with at least one other, and I once went on a course with 16 participants; 10 of them women and four of those called Sue! But I don’t know anyone under 35 with my name. On the other hand, my son was a preschool with two children called MacKenzie and three called Tyler (it was a very small preschool)!

Pingback: The power of names: picturing the past | Shaking the tree

The Scottish naming pattern has helped me identify missing children many times also. Such a great resource to understand this tradition.

Isn’t it; I remember my mum trying to explain it to me once, but that was before I was really “into” family history and it went in one ear and out the other. I feel very lucky I read Judy’s post on the subject when I was starting out; it’s been invaluable. 🙂

Su – what is this connection we have? First the post on children and your mention of the Foundling Hospital. Then just now, when you “liked” my post, I noticed in the “great posts worth seeing” list on the “like” notification email that you wrote about naming patterns last month. Are we related? Do we share some ancestral memory? (That’s the topic I’m writing right now.) I’m not settling for the “great minds think alike” banality.

Anyway, you are clearly a deep thinker. I appreciate your sharing thoughts.

I don’t know! I’ve just referenced one of your comments in a post about street photography. As I was reading your post on naming, I realised it added so much to my understanding of the wider history of names. We’ll probably never know if we’re related. My family history looks like coming to a halt at the 17th century. My ancestors were poor and landless, and so mainly appear in church records. Parish records were very sporadically made during the 17th century, and almost non-existant before that, so I will be extremely lucky to trace more than 10-11 generations. But hey – I’m happy with that. It’s the social history that excites me more than the names and dates.

Pingback: We, the Dragons, shall live, for all eternity! | Wired With Words